Jerome K. Jerome wisely pointed out that you could either be a rider of bicyles, or someone who overhauled them. He knew it was folly to mix the two enthusiasms.

It's the same with people enjoy music. There are those who quest for technical perfection, both in performance and recording, and others who simply enjoy listening to music that lights the touchpaper of thought and emotion.

I'm squarely in the latter camp. I couldn't give a donkey's toenails whether a piece is technically irreproachable and recorded with glacial clarity. What I'm interested in is how it is interpreted. And if something wonderful is played to me amidst the (digitally remastered) scratches and crackpopples of a 78rpm record - like Beecham's breathtaking Zauberflöte - then that's just fine by me.

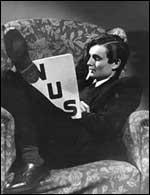

Even so, nothing prepared me for my first encounter with Glenn Gould. Sure, I'd listened to and admired lots of Bach. I'd also listened to enough pianists that I was starting to pick out favourite performers, notably Vladimir Ashkenazy, Maria João Pires and - above all - Clifford Curzon.

Then, when I was 15 years old, someone lent me a tape of Glenn Gould playing this interpretation of Bach's Goldberg Variations. Listening to it was like sitting in a bathtub filled with sweet cocktails whilst someone chucked in a three-bar fire.

Yes, you can hear Gould humming. But I'd rather listen to that any day than endure the coughs of the concert hall, or witness the smug little notes that vulgarians pass from one to another when listening to classical music in public.

Listen. Hum yourself. Then, when you're thoroughly hooked, go and listen to this and watch all of these. And remember that perfection is always flawed.

Although I most admire Gould's 1981 recording of the Goldberg Variations, I strongly recommend you compare it with his groundbreaking 1951 performance. The differences of style and insight between the two are startling.